Chlorine: A weapon of last resort for ISIL?

Over the past few weeks several press reports have suggested that the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) have resorted to chlorine use in attacks in Iraq and Syria.

The grouping is no stranger to chlorine. In some earlier incarnation it was known as al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) and later it rebranded itself as the Islamic State of Iraq when it explicitly began trying to control territory. Harsh imposition of its strict interpretation of Sharia law and extreme violence towards anybody refusing total subjugation to its rule soon had Sunni tribal leaders uniting in resistance early in 2007. They also began cooperation with forces of the US-led coalition occupying Iraq since 2003 and the Shia-dominated Iraqi government. AQI started mounting large-scale operations involving several hundreds of fighters to capture local seats of power. During the first half of 2007 suicide attacks with lorries rigged with a large quantity of explosives evolved from isolated incidents to terrorise and destabilise societies to a tool integrated in assaults against government centres and fortified positions. After an isolated attempt in October 2006, AQI launched almost 20 chlorine attacks in the first half of 2007.

This posting is a first effort to understand the dynamic behind ISIL resorting to chlorine and perhaps some other toxic chemical substances in military operations in Iraq and Syria. If current chlorine attacks can be confirmed, then some interesting parallels with the brief episode in Iraq may be discerned (but the hypotheses do require further study to be confirmed):

- Chlorine attacks occur when efforts to subdue the local population or make new territorial gains falter.

- The principal aim of the agent’s use appears to have been psychological impact and social disruption. Its net result was bolstering social resistance and local people’s assistance in detecting AQI armament workshops.

- AQI never succeeded in deploying chlorine successfully in support of tactical operations. Forces aware of the possible use of chlorine in combat are unlikely to waver. Delivery by projectile would fail to create sufficiently dense clouds, be highly imprecise in terms of targeting, and the cloud’s visibility enables timely evasive action. Moreover, in Iraq the chlorine did not cause a single fatality.

- ISIL, like its earlier incarnations, does not have an indigenous chemical weapon (CW) programme. It depends on capturing military bases to replenish its advanced conventional armaments, and any success in slowing down its territorial gains severely degrades its technological edge over its opponents. It would similarly depend on existing stocks or transports of liquid chlorine to support a sustained CW campaign. Depletion of chlorine supplies at water processing facilities combined with strict management of chlorine transports by provincial Iraqi authorities contributed to the swift end of the attacks (but also to an upsurge in cholera cases).

Genealogical snapshot

In 2003, following the US invasion and occupation of Iraq, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi became one of the prominent leaders of the Sunni Salafist insurgency as head of the Organisation of Jihad’s Base in Mesopotamia. The next year he pledged allegiance to Osama Bin Laden and his grouping became better known as al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) or al Qaeda in Mesopotamia. One month later, in November 2004, AQI was one of the principal forces in the battle of Fallujah, which became notorious for the allegations of US use of white phosphorous as an anti-personnel weapon. A piece in the US Army’s Field Artillery magazine (March–April 2005, p. 26) described the use as ‘“shake and bake” missions at the insurgents, using [white phosphorous] to flush them out and [high explosive] to take them out’, a description not entirely shared by embedded journalists. The battle became an insurgent rallying cry. AQI founded the Mujahideen Shura Council to unify all Sunni insurgency groupings in January 2006, which was followed in October by the declaration of the foundation of the Islamic State of Iraq. Abu Omar al-Baghdadi proclaimed himself as Emir. AQI became responsible for some of the deadliest suicide bombings and sectarian infighting in Iraq.

Abu Omar al-Baghdadi was reportedly killed in a US-Iraqi raid in April 2010, after which the grouping declined. He was succeeded by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in May, who reconstituted AQI (notably with senior military and intelligence figures from Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath party) and achieved renewed prominence after the US withdrawal from Iraq. His fighters operating in Syria became the core of the al-Nusra Front (Jabhat al-Nusra). This organisation together with AQI then (kind of) merged into the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, better known as ISIL, in April 2013. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi proclaimed a worldwide caliphate with himself as Caliph on 29 June 2014. He shortened the grouping’s name to the Islamic State.

Allegations of chlorine attacks in Iraq (2006–07)

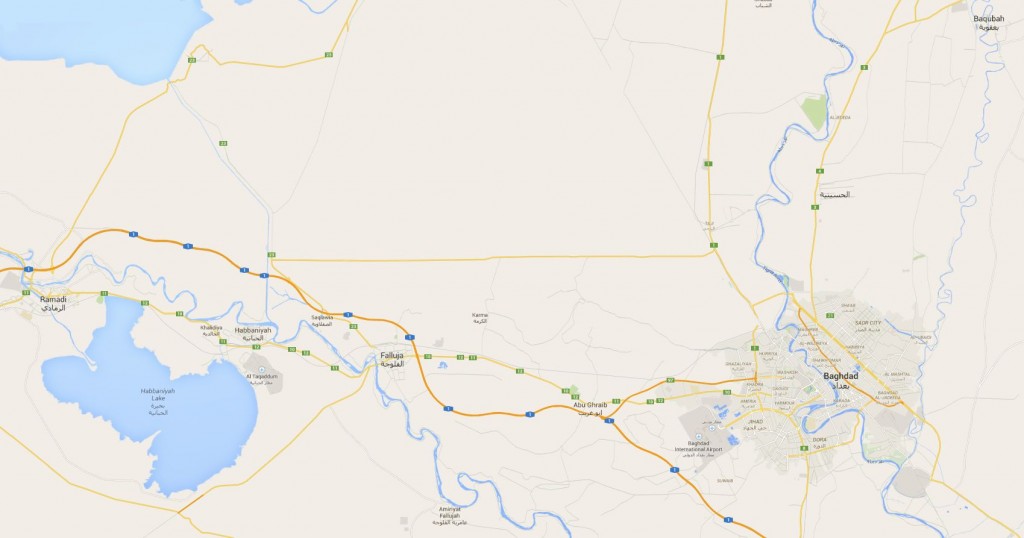

In Iraq all chlorine attacks appear to have been concentrated in a triangle linking Baghdad with Fallujah and Ramadi to the west and Baqubah to the north. The Sunni insurgency was particularly strong in this area. Ramadi, capital of Anbar Province in western Iraq, was of great strategic importance to AQI, because the principal roads linking Baghdad to Jordan and Syria converged on the town’s western edge. In Baqubah AQI laid the territorial foundations of the future Islamic State. As the ground they controlled expanded, they began to systematically impose the writ of the Islamic State of Iraq based on a very strict interpretation of Sharia law that brooked no tolerance for other religions or even Islamic sects.

Unless specifically attributed, this section draws on searches in the LexisNexis database of press reports.

- The first documented chlorine bombing involving a car bomb carrying two 100-pound chlorine tanks and fitted with twelve 120mm mortar rounds injured three Iraqi policemen and one civilian in Ramadi on 21 October 2006. This incident, however, does not appear to have been publicly reported until June 2007. The link to al Qaeda and affiliated groups was made retroactively. No further chlorine incidents seem to have taken place until the end of January and February 2007. They were being mentioned in association with, but not yet directly connected to the rise of AQI.

- A suicide attack with a chlorine tank and explosives on a lorry in Ramadi on 28 January 2007 killed 16 people. All died as a consequence of the detonation.

- Another suicide bombing, also in Ramadi, took place on 19 February. Few details about this attack and its consequences have been reported.

- The next day, 20 February, a tanker carrying chlorine for water purification exploded outside a restaurant in Taji, killing six and injuring over 100 Iraqis. Taji is about 30km to the northwest from the centre of Baghdad.

- On the 21st a similar incident took place along the road from Baghdad International Airport and the western part of the capital, killing two and wounding at least 32 others. By this time military and press reports firmly linked the chlorine attacks to AQI, but military officials commenting on the new development still speculated on whether other insurgent groups might be copycatting the attacks with toxic chemicals.

- That same day, raids by US forces in Karma northeast of Fallujah uncovered a workshop with chlorine canisters, other chemicals, and a variety of guns, rockets and ammunition. Three vehicles were in the process of being reconfigured as car bombs. and they found chlorine can steps.

- On 16 March AQI launched a double chlorine attack. A suicide bomber detonated the first car at the entrance of a large housing complex on the edge of Amiriyat south of Fallujah. Six civilians and two police officers died in the blast, but some 100 people, including several children, reported a variety of symptoms from exposure to chlorine. These included vomiting and irritation of the respiratory tract and skin. The second explosion occurred in the Albu Issa tribal region, also south of Fallujah. The US military counted around 250 Iraqi civilians suffering from poisoning. Six soldiers also received medical treatment for chlorine exposure. The driver reportedly fled just before the detonation. (A third more or less simultaneous suicide bomb attack took place in Ramadi, but it is unclear whether in this instance any toxicants were released. Some press accounts mention three chlorine bombings, but offer no details on the Ramadi attack. The reported casualty tally equals that of the first two bombings.)

- Seven days later, on 23 March, Iraqi police stopped a lorry that, according to a briefing on the 25th, was rigged with two tonnes of explosives and contained 5,000 gallons of chlorine. The driver was held for questioning.

- Two chlorine bombings on 28 March targeted a government complex in Fallujah. The assault started with mortar fire at 6:33 a.m., followed by the lorries. Firing at the first vehicle, Iraqi police manage to detonate it before it reached its target. Shortly thereafter they managed to destroy the second lorry also by means of small arms fire. This was the first attempt at a coordinated attack with CW on a single target. 57 Iraqi personnel and 14 US soldiers were injured by the blasts, according to a Department of Defence briefing on the 30th. Many Iraqi policemen required medical treatment for symptoms typical of chlorine poisoning.

- Friday, 6 April witnessed another attack in Ramadi. Original reports indicated that 27 people, including 2 police officers, had died instantly and another 30 suffered injuries. US military officials later revised the figures to 12 fatalities and 43 wounded. Fifty bystanders required medical attention for breathing difficulties in a nearby hospital, according to a local doctor. It occurred in the late morning as people were waiting for noon prayers. The victims included many women and children. The driver targeted a police station, but blew himself up about 200 metres away next to a market in a residential area. Apparently Iraqi police fired at the driver as he was speeding towards a checkpoint. The load consisted of a large volume of chlorine and explosives, which had been covered with sacks full of fertilizer to enhance the blast.

- On 20 April, US-led coalition forces found seven tanks of chlorine during a raid near Mahmoudiya in Babil province south of Baghdad. In an article published on 30 April, Max Boot reported having been shown a document summarising arms captured from AQI by a US Colonel. The list included 6,000 gallons of chlorine. (The article did not specify the precise time frame during which the weapons were captured.)

- After some weeks without fresh chlorine incidents, on 25 April a lorry loaded with toxic agent was detonated on the Western outskirts of Baghdad. One person was killed and two injured.

- Five days later, on 30 March, Ramadi was struck again, resulting in 6 dead and 10 other casualties.

- On 15 May, a bombing involving chlorine release hit an open air market in Abu Sayda at about 8p.m. Thirty-two people died and some 50 were reported injured, many suffering from exposure to the toxicant. This attack was unusual as it took place to the northeast of Baqubah, far removed from the area where the bulk of chlorine strikes had occurred previously. Diyala province has a mixed Sunni and Shia population. Associated Press cited a hospital official who said that his hospital had received three bodies and 11 wounded, who all showed symptoms of chlorine poisoning. (Given that a US military spokesman denied chlorine use, close reading of the article suggests that the fatalities did not result from toxic agent exposure.)

- On 20 May, the mayhem returned to Ramadi area. A suicide attack involving a lorry loaded with chlorine against a police checkpoint to the west of the city killed 11 people, including 6 policemen, and wounded 22 others. A hospital treated 30 additional people for respiratory problems caused by the chlorine used in the bomb.

- The final chlorine attack during the US military occupation of Iraq took place on 6 June. It was the second one in Diyala province and targeted a US forward operating base northeast of Baghdad. The car bomb detonated about 200 metres from the base entrance, unleashing a cloud of chlorine gas that sickened at least 62 soldiers but caused no injuries.

- Coalition operations on 5 July uncovered another chlorine vehicle-bomb making site north of Taji. Soldiers from the Multinational Division Baghdad secured two tanks filled with the toxic chemical.

There was one other reported incident involving chlorine in Sadr City, a Shiite suburb of Baghdad, on 14 April 2007. One resident died and 11 were sickened after a neighbourhood water tank was tainted with chlorine. Arab newspapers, including Al-Mada (Iraq), subsequently confirmed a technical malfunction in a water-processing plant and raised the number of people taken ill to 24.

Making sense of the AQI chlorine attacks

On the whole it seems that the chlorine bombing campaign in Iraq was designed more to augment their own fearsome reputation in order to subdue a population in the territories challenging AQI control or to unsettle and confuse less well trained units, such as police forces. Ihsan Muhammad al-Hasan, professor of sociology in Baghdad, linked the resort to CW to the success of counter-insurgency operations by US and Iraqi units, which blunted AQI tactics. Interviewed by Al-Zaman, an Iraqi newspaper, on 2 May, he explained that:

terrorism started to use modern ways to cause severe injury to people and to produce psychological effects and generate a state of confusion on the psychological and social levels. He said that its impact on the person who is close to the site of the explosion results in skin burns that poison the victim and then cause his death as a result of inhaling chlorine gas. He said that many citizens are afraid of leaving their homes to go about their daily business out of fear of bombings that employ this substance and its severe impact on them. Many shops have closed as a result of acts of violence, murder, and displacement. Also, businessmen and others have refrained from doing business, which causes big losses to the Iraqi economy. He spoke about the social and economic effects, saying: Citizens and state agencies alike should act to face this problem through social and political awareness and discover the persons who are responsible for these acts and hunt them down to know the places where these chemical bombs are produced and the parties that are supplying them with chlorine gas, whether they are internal or external, and expose them in the media. (Translated from Arabic by BBC Worldwide Monitoring, retrieved via LexisNexis.)

The escalation to coordinated chlorine bombings in AQI attacks seems to confirm this hypothesis.

Al-Hasan’s appeal to citizens to actively resist AQI’s intimidation tactics most likely points to the reason why the escalation happened in the first place. Anbar Province, which suffered most chlorine strikes, is a predominantly Sunni tribal area. At the start of 2006 AQI stepped up its programme to bring the tribal leaders under its control, thereby increasingly resorting to intimidation and outright violence. By the end of spring those tribal leaders had begun to enter into alliances to resist AQI, and, more importantly, they opened up to security collaboration with US forces and Iraqi security units. The swell eventually became known as the ‘Anbar Awakening’ and succeeded in drastically reducing the AQI murders and other forms of violence. The next year, however, AQI started mounting large raids involving several hundreds of fighters against tribal leaders and other influential individuals calling for resistance against the proposed Islamic State of Iraq. They were accompanied by suicide attacks involving heavy lorry-mounted bombs. The chlorine fitted into this escalation.

Insurgent access to chlorine stocks was not unlimited, however. AQI elements raided the water plants in the Anbar Province west of Baghdad to steal the chlorine. At the height of the chlorine bombings in April 2007, the New York Times reported that Iraq was importing the chlorine for water purification from Jordan and Syria. The insurgents thus also seized the lorries en route to Baghdad, as a consequence of which Anbar Province officials intercepted the shipments in order to organise protected convoys. The Al-Zaman article cited above noted that the sale of liquid chlorine had dropped considerably as a consequence of the interruption of importation from neighbouring countries. It also quoted Abd-al-Karim Khalaf, official spokesman at the Interior Ministry, who said that the travel of business trucks in Baghdad had been limited and some service exceptions for government departments. Direct orders had been issued to detachments and checkpoints to search all trucks and to make sure that they have official documentation. A press report published on 23 September quoted Iraqi officials as saying that ‘as much as 100,000 tons of chlorine was being held up at the border for fear it would be hijacked and used in explosives’. The countermeasures, however, contributed to an upsurge of cholera cases in Iraq as a consequence of reduced water treatment.

Apart from transitory irritation problems, the chlorine does not appear to have been responsible for any fatalities or major injuries, even though some bystanders required hospital admission. Heat from the detonation and shearing forces would have destroyed much of the chlorine, particularly during the first attacks when the vehicles were rigged with an excess of explosives. In contrast, blast and projected shrapnel hit bystanders full force. Most likely chlorine contributed to the overall confusion caused by the detonation and may have hampered rescue efforts. The coloured gaseous cloud and poignant smell, never knowing whether another substance than mere chlorine, would have intimidated any person not trained to operate in a toxic environment. As testified by Professor al-Hasan, the population had by then adopted a mind set of resistance to AQI and were therefore less inclined to be intimidated by further escalation of violence. They worked together with US and Iraqi forces to dismantle AQI cells and hideouts. Khalaf, the Interior Ministry spokesman, also remarked that citizen vigilance actually helped to defuse a booby-trapped lorry laden with chlorine.