Disarmament education: Road-testing a master’s course on CBRN dual-use technology transfer controls

From 17 until 28 June I ran an Executive Course on Export Control at the M. Narikbayev KAZGUU University in Nur-Sultan (formerly Astana), Kazakhstan. Its goal was twofold. First, it tested in a real university setting parts of a master’s course on chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) dual-use technology transfer controls I have been developing since February 2018. Its second purpose was to attract interest in organising the full master’s course from other Central Asian academic institutes.

Set in the broader context of peace and disarmament education, the Executive Course posed considerable challenges from the perspective of educational methodology and the participants’ varied professional and cultural backgrounds. Contrary to many vocational training initiatives in treaty implementation assistance or strengthening treaty norms, the Executive Course (and the fuller master’s course on CBRN dual-use technology transfer controls) sought to deepen the general understanding of the security concerns about dual-use technologies, make participants understand how these might affect their own work and responsibilities both as a professional and an individual, and help them to identify and address issues of dual-use concern. As a general conceptual framework, the recommendations presented by the Advisory Board on Education and Outreach (ABEO) of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in its Report On The Role Of Education And Outreach in Preventing The Re-emergence of Chemical Weapons (OPCW document ABEO-5/1, 12 February 2018) guided both the preparations and the conduct of the Executive Course.

This blog posting introduces the master’s course, describes the preparations for the Executive course, identifies challenges that emerged in the planning phase and while the course was underway, and discusses how they were overcome.

General background

The development and running of the master’s course make up one of the key work packages of the Targeted Initiative on Export Controls of Dual-Use Materials and Technologies. The European Commission, Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development (DEVCO) funds the programme in support of the European Union’s Global Strategy (2016) and Strategy Against the Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction (2003). Its implementation has been entrusted to the International Science and Technology Centre (ISTC) and the Science and Technology Centre in Ukraine (STCU). ISTC, located in Nur-Sultan, targets Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Armenia, Georgia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Mongolia), whereas the Kyiv-based STCU serves the GUAM countries (Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Moldova).

The Targeted Initiative identifies government officials, universities and academia as the key customers for the university course. The three groups comprise many different types of professional expertise and experiences. Moreover, the countries in which the ISTC and STCU deploy projects present a rich cultural and educational variety.

From the outset, the design of the master’s course took the different professional competencies and national cultural and educational diversity into account.

Designing the master’s course

As noted, the Targeted Initiative envisages a plurality of nationalities and professional backgrounds for the university course. Working to optimally implement the Chemical Weapons Convention and reinforce the norm against chemical weapons, the OPCW faces similar challenges, only on a global level. One of the key ABEO recommendation holds that target audiences need to discover the issues for themselves, how those issues affect their work, and, as a consequence, why they should be seized by them. Answering those questions represents a major educational process in its own right. Furthermore, educational exercises showed that each one of the professional categories may have specific awareness of issues relevant to their work field, but people may not realise that colleagues and partners from other disciplines can face similar challenges in different contexts. Consequently, besides being multi-disciplinary, the course also has to be cross-disciplinary.

A second design parameter is the need for the master’s course to fit a variety of educational situations. Government people might want to obtain a certificate of attainment within the shortest time frame; universities might prefer to integrate the lectures on technology transfer controls in broader educational programmes, such as economics, international law, science education, political science, and so on. University students could be interested in certain aspects of the course and therefore prefer to study them as an elective.

In the early stages of the project both ISTC and STCU identified academic institutions as potential partners in the project, and cooperation was quickly established with respectively KAZGUU University and the Taras Schevchenko National University, Faculty of Economics in Kyiv. ISTC and STCU also intend to offer the university course to their respective partnering countries, which reinforced the need for design flexibility to meet local legal and administrative criteria for new courses and take into account their primary student populations.

To maximise flexibility, an early decision was taken to design the full university master’s programme as a set of self-contained modules that could be offered both as a standalone course or as individual components. In the latter case, a university could choose to integrate some or all of them into a larger master’s course or offer them as electives or as a specialisation. Professionals (e.g. government functionaries) could take all modules and be rewarded with a certificate of attainment after fulfilling all requirements.

The modular approach offered an additional benefit, which gradually emerged while development of the master’s course was progressing. As the discussions on how to use the modules became more concrete, the question of transfer of their ownership arose. While under the Targeted Initiative an academic institution is offered a fully developed master’s course, the participating institution must also commit itself to teaching the selected modules over the coming years. Since each module has a specific focus, they can be taught by different professors with the appropriate specialisation. Thus, in a project presently in an advanced stage, visiting professors are to be contracted for two academic years. During the first year, they will teach their assigned module and assist a local professor who will eventually take over with course content and methodologies. The local professor will assume teaching responsibilities in the second year while the visiting professor will be available for any required assistance. The assistance is ambitious in its own right as it should enable the local professors to participate in international forums on dual-use technology transfer controls and expand their expertise. The modular approach thus creates a group of local professors who can take over the master’s programme and develop it further depending on future demands and ambitions.

In summary, the master’s course has to be adaptable to a wide variety of educational situations, ranging from regular university teaching (including training of local lecturers) to condensed or highly specific specialist courses.

Identifying the issue areas

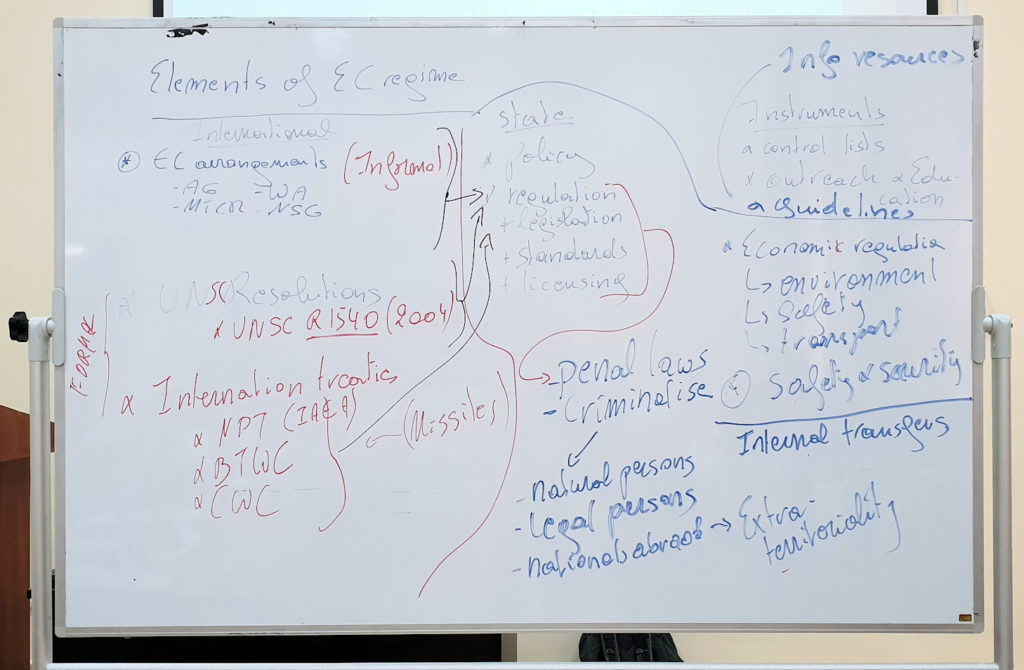

Mind mapping technology helped with the identification of the issue areas central to the envisaged university course and establishing links between them. The following main branches in the mind map came to the fore:

- Basic knowledge about the CBRN spectrum and core concepts in transfer controls;

- Core knowledge about the concepts of ‘technology’ and ‘dual-use technologies’;

- International legal and regulatory frameworks governing CBRN-related dual-use technologies;

- Understanding of the responsibilities of states, institutions and individuals in the prevention of misuse of technology;

- Threats and risks related to dual-use technologies;

- Education and outreach with regard to the prevention of the misuse of dual-use technologies;

- Dynamics of transfer controls, the roles of different professional and actor categories, and resources for information on laws, regulations, and implementing agencies; and

- Economic relationships, covering domestic and international partners and technology transfer patterns.

Nine educational modules were crafted based on these insights: 2 introductory, 4 substantive, and 3 seminar modules:

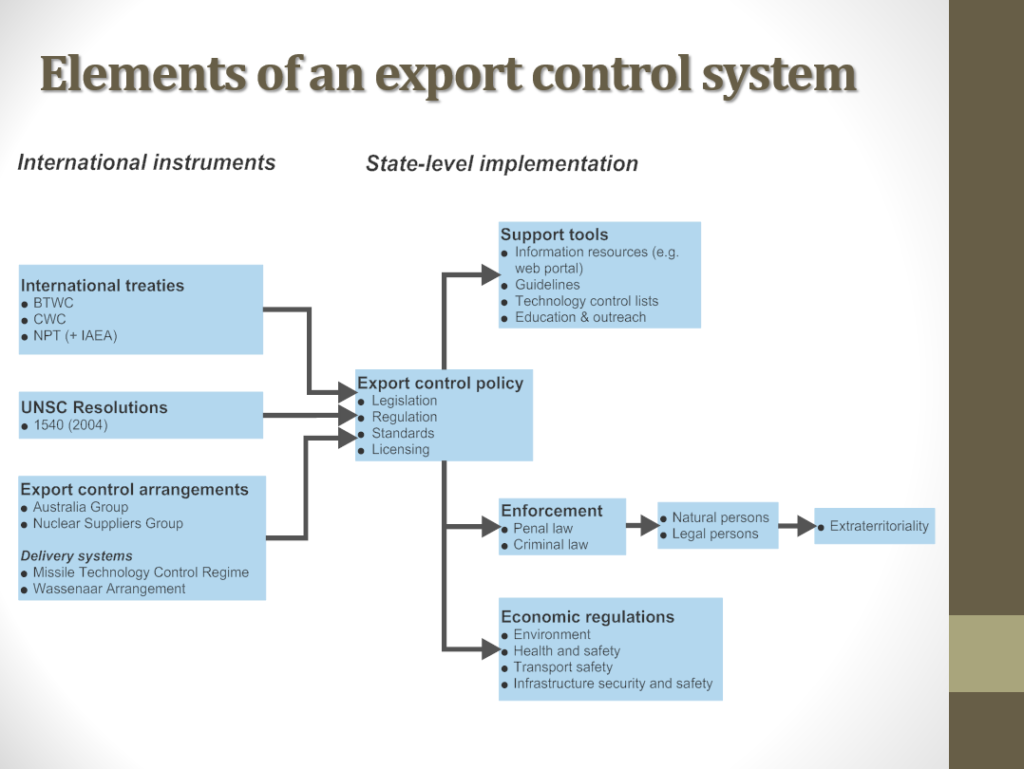

- Introductory module 1 ‘CBRN basic knowledge and concepts’ introduces course participants to the basic concepts relating to CBRN weapons and their control; the concept of dual-use technologies and the challenges they pose from a policy perspective; and the formal, multilateral treaties and other arrangements set up to prevent their misuses.

- Introductory module 2: ‘Frameworks, instruments and responsibilities’ aims to provide a holistic overview of frameworks and instruments relevant to CBRN export controls, their respective objectives and areas of operation. At the same time, those instruments engender responsibilities for different categories of actors. The module offers an introduction to those responsibilities and links them to broader societal and policy contexts.

- Substantive module 1: ‘Threats, risks and their mitigation’ offers in-depth analysis of the various ways in which threats and risks related to CBRN materials and technologies may present themselves. It discusses the various processes through which technology transfers may deliberately or accidentally occur. It connects threats and risks with the various frameworks and instruments to counter them and, by way of introduction, to roles played by various national implementors and national and international actor categories.

- Substantive module 2: ‘Transfer controls (International)’ shifts the focus to the international regulatory level. The historical analysis not only informs students of the origins of export control regulations, but also places their evolution in the context of international developments. The module furthermore discusses the various instruments available to a state to prevent and penalise proliferation activities. Finally, it engages students on the importance to educate key stakeholder communities on their specific contributions or responsibilities regarding the prevention of CBRN proliferation.

- Substantive module 3: ‘Transfer controls (national requirements)’ shifts the focus to the national regulatory level. Such national obligations may have different sources: international treaties, membership of international organisations, UN Security Council Resolutions, membership of regional organisations (e.g. economic zones, Nuclear Weapon Free Zones, etc.), and so on. Finally, it also informs students of how specific international obligations assumed by a country are transposed into national legislative and regulatory frameworks, and how they are implemented.

- Substantive module 4: ‘Promoting responsible behaviour’ informs course participants how they in their professional capacity or as an individual can contribute to raising awareness, education and outreach. Such contribution can come in many forms, including the design of such activities, the promotion of such activities in a person’s professional environment, or the actual running of such activities. This module therefore also supports the continuation of the master’s programme and the building of local stakeholdership in it.

- Seminar module 1 reinforces the objectives of Substantive Module 1. It could engage students in two ways. First, they can relate to the issue areas they believe affects them most and identify the types of actors with whom they should interact to prevent proliferation. Through group discussions they can explore how a similar issue may present itself to different actors and discover whether another person’s insights and experiences may be relevant to one’s own context. Second, students can be exposed to and familiarise themselves with very specific national and international tools (such as internet resources).

- Seminar module 2 (follows Substantive Module 3) could present course participants with certain scenarios that they must resolve using the national regulatory frameworks and institutions. Discussions could, for instance, lead to the identification of gaps or opportunities for amelioration, thus leading to policy options and their justification.

- Seminar module 3 can combine two objectives. First, students can be exposed to (experience) various educational strategies and acquire practical insights into their design and objectives. A second part of the seminar can be dedicated to interactive review of the whole course and preparation of the dissertation, etc.

Each module represents a full week’s worth of teaching. However, the hosting university will decide the exact number of hours of teaching and course work.

The Executive Course: From concept to practice

Nevertheless, theory and practice may diverge considerably. Hence the importance to test the master’s course.

The Executive Course at KAZGUU University reflected the Targeted Initiative’s core audience perfectly. It brought together 21 university professors and academics (mostly law and economics), scientists, government officials and national export control practitioners, experts from regional international organisations, and students. They arrived in Nur-Sultan from Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Pakistan, and Uzbekistan.

The mix of participants may have been perfect, it also posed a considerable set of educational challenges. How well was each participant versed with international security, armament and proliferation, disarmament and non-proliferation, technology transfers, risk assessment and risk management, relevant international and national law, and so on?

Knowledge of English was a prerequisite for course registration, yet uneven understanding of the language could affect teaching. Knowing a word is one thing; understanding the concept behind it is something else altogether.

From the outset, it was clear that different educational strategies had to be deployed. Yet, unknown until the course actually started was how comfortable participants would be with those strategies in view of educational practices in their respective countries. Would they view a lecturer as an authoritative source of information and wisdom or rather as an interlocutor assisting them in their discovery and understanding of issues?

In summary, individual lectures could be planned but final preparations would have to wait until the course was underway. The first few days would entail some level of methodological experimentation before the adoption of a more settled approach. Even then, on-the-spot adaptation or even improvisation could not be ruled out, requiring anticipation of backup options.

Fortunately, I did not have to face those challenges all by myself. During the first week I enjoyed the assistance of Professor Maria Espona (Co-director of ArgIQ – Information Quality in Argentina). Dr Kai Ilchmann (Arms control consultant in Germany, research fellow at the Harvard Sussex Program on Chemical and Biological Weapons at Sussex University, UK, and formerly a professor at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) and Dr Kamshat Saginbekova (KAZGUU University and recipient of a Doctoral Research Grant at University of Liège, Belgium) joined me for the second week.

All three colleagues have experience with teaching in cultures outside of Europe or North America, or are familiar with Central Asia. Personally, I gained conceptual knowledge and practical experience through outreach and education projects in Africa when Director of the BioWeapons Prevention Project (2003-08), while teaching a regular seminar on disarmament dynamics to a multinational class at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva (2004-08 and 2014), and as a member of the OPCW’s ABEO since 2016.

Course set-up

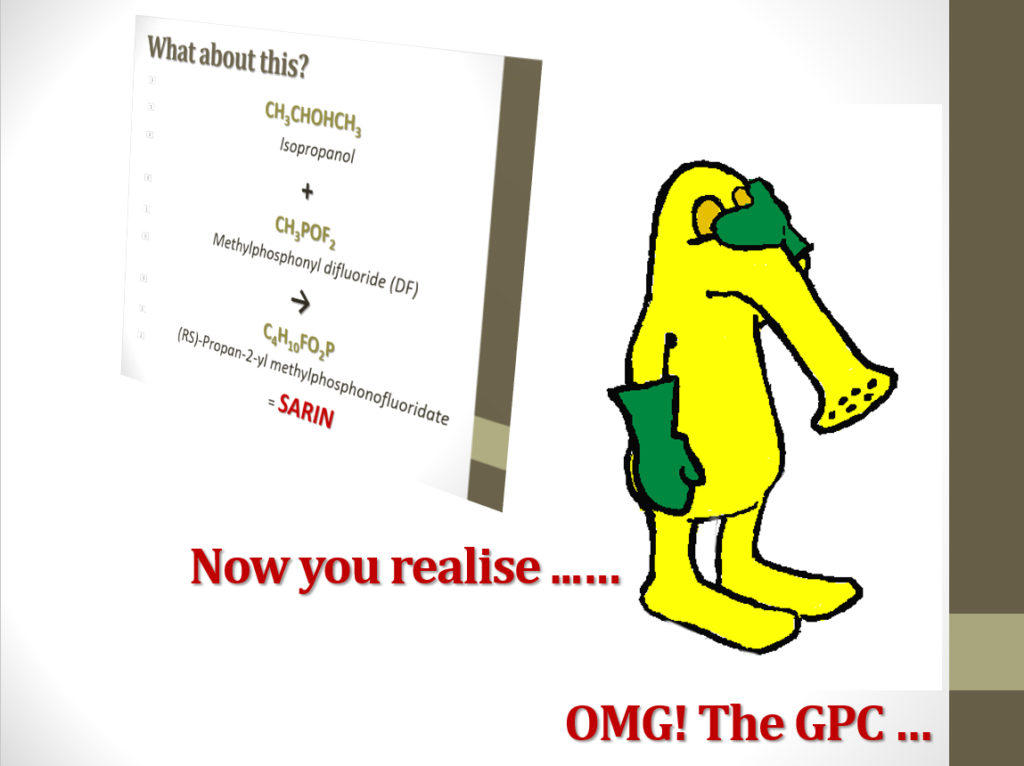

Contents for the two-week Executive Course were mostly drawn from both introductory modules. Some lectures focussed on broader contextual elements, including an introduction to CBRN weapons; the armament dynamic and the role of technology transfers in its continuation; the differences between state-run and terrorist armament dynamics and technology acquisition processes; the international legal context for constraints on CBRN weaponry; technology and dual use; tangible and intangible technologies; (infrastructure) safety and security; science and technology development; risk assessment and risk management; and core concepts (such as the General Purpose Criterion, catch-all principle, etc.).

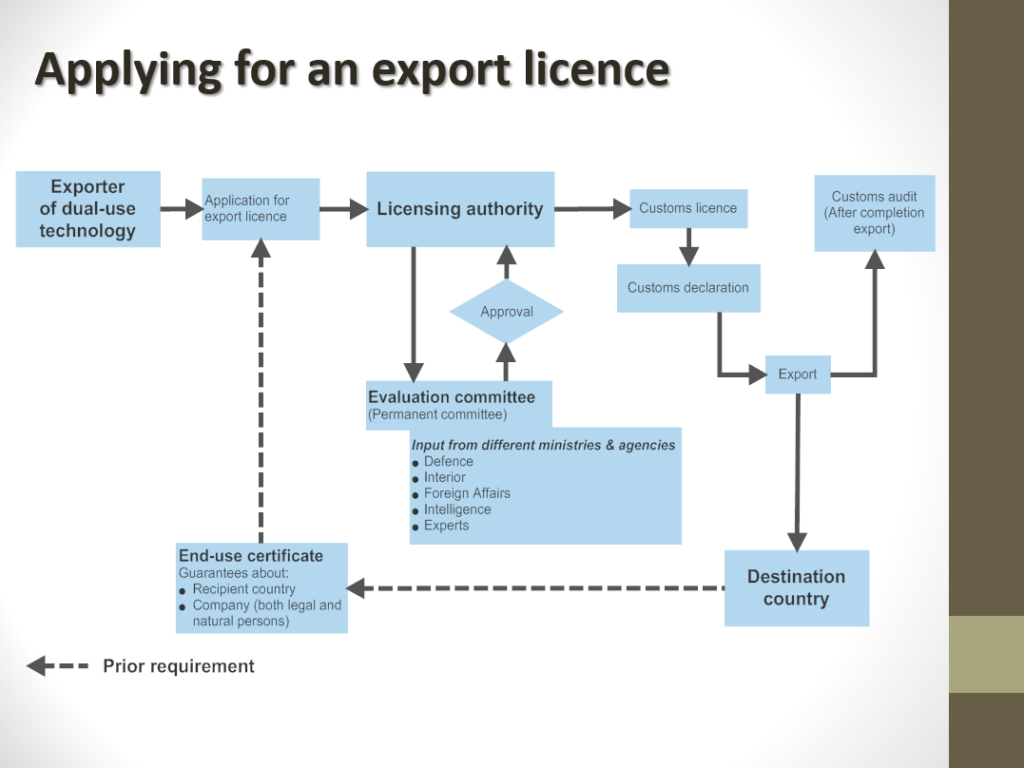

Other lectures were designed to let the participants discover the issues, including how a state’s controls on technology transfers are governed by a wide range of international obligations and how such obligations need to be transposed into national legislation and regulations. Certain exercises were specific. Departing from case studies, students had to build for themselves the export control process, identify the partners (actors) in an export of dual-use goods, and discover the types of regulatory tools required to prevent a real case of illicit exports from the 1980s from recurring again. The controversy surrounding the H5N1 (avian influenza) gain-of-function research and the subsequent imposition of a research moratorium was used to illustrate how even publication of results in a journal may turn into an export control issue.

Teaching ran from 9 am till 1 pm and from 2pm till 5pm. Each morning session lasted 105 minutes; the afternoon ones 75 minutes. Between sessions there was a 30-minute coffee break.

Test-running the course

The educational plan envisaged a mix of lectures and interactive teaching to let participants (split into 3-4 breakout groups) discover issues and understand their implications via specific assignments. Programme modifications were anticipated, and contingency plans drawn up. With the course underway, there was permanent evaluation, including during the coffee and lunch breaks. Especially during the first week, as they were familiarising themselves with the participants and their backgrounds, the lecturers sometimes tweaked their presentations during such breaks. In a few cases, they completely redesigned planned lectures overnight. In one specific case, I altered the end of one lecture during a coffee break, moved one scheduled for the second week to follow immediately after the altered lecture, and let it segue into interactive working group discussions that lasted for three sessions spread over as many days.

It proved to be the breakthrough moment. Afterwards, course participants comfortably participated in interactive sessions that deepened their understanding of relevant issues.

Enhancing interactive education methods

The early lectures were context setting. They aimed to provide participants with broad background knowledge concerning armament and proliferation, disarmament and non-proliferation, and the differences between armament dynamics in states and in non-state entities. Vocabulary and technical terms got clarified. Across the two weeks all lecturers repeatedly returned to core vocabulary (e.g. general purpose criterion and catch-all principle, tangible versus intangible technology, dual use, etc.) as part of a pre-agreed educational methodology.

Language proved a challenge, but not an insurmountable one. Arguably, it was not even the biggest one. When in the middle of the first week Maria Espona introduced the first major exercise in the form of a gap analysis to familiarise the audience with the different types of laws and regulations supporting an effective export control mechanism, a broad lack of familiarity with research tools came to the fore. A week-long basic export control course (also part of the Targeted Initiative, but unrelated to the development of the master’s programme) run in Kyiv in May had given a foretaste of the problem. Certain aspects of the lectures under preparation for the Executive Course were subsequently adjusted in function of the experiences in Kyiv. However, the breadth of the problem as it revealed itself in Nur-Sultan carried risks for the educational objectives. One option considered during the weekend break was to insert a lecture and exercises in structured searches on the Internet during the second week. It was eventually implemented in preparation of a recapitulative exercise (see below).

Another alteration, however, I made on the spur of the moment. The final part of a double session on ‘Threats, risks and their mitigation’ on the first Thursday morning intended to guide students to the next major theme of the Executive Course, national implementation of international obligations against CBRN proliferation. Instead, similar to the previous day’s gap analysis exercise on international obligations, it revealed very uneven awareness of economic actors and national regulatory frameworks.

As part of the transition to national obligations, the afternoon was scheduled to begin with a case study on the proliferation network that supported the construction of a CW factory at Rabta, some 85 kilometres south of the Libyan capital Tripoli, during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Those events unfolded when the Australia Group was beginning to recommend more comprehensive and better coordinated national export regulations against chemical and biological weapons (CBW) and before the finalisation of the CWC negotiations (in September 1992). The case study thus sought to highlight proliferation risks in the absence of a universally accepted prohibition and inconsistent implementation of commonly agreed export controls. A plenary discussion on which economic actors take part in technology transfers and how present-day laws and regulations ought to prevent recurrence of the Rabta case was to follow the presentation.

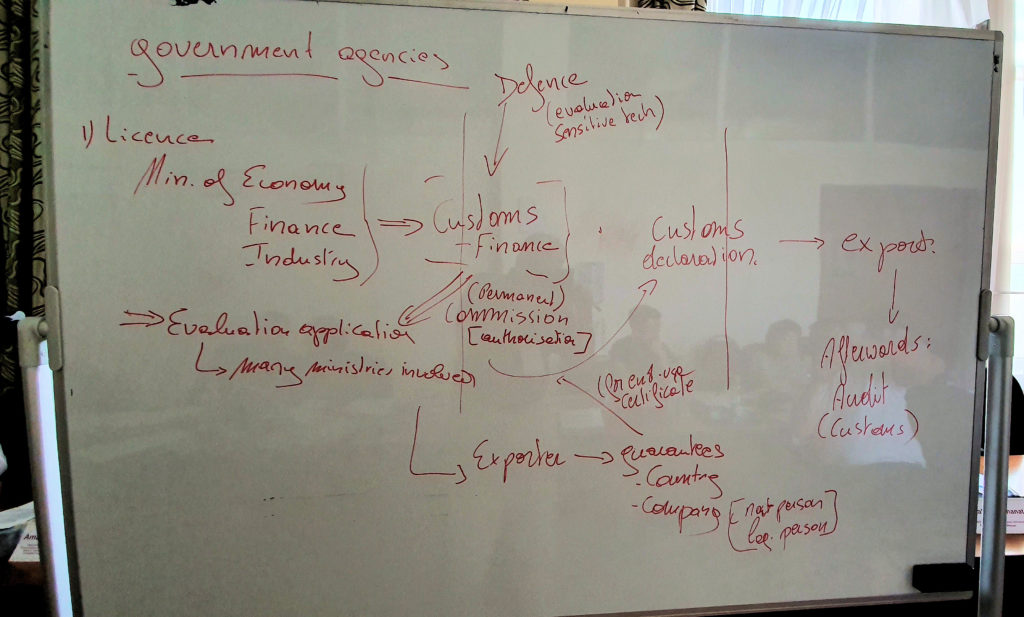

In view of the outcome of the morning sessions, over the lunch break I replaced half of the slides in the original presentation with five questions (see picture above). The new objective was to have breakout groups explore each question in succession through pooling knowledge and expertise. Then each group had to present its answers and for each question, the most important points were collected in a structured way on a whiteboard. Next, all participants collectively drew up a flowchart logically linking the various points.

While the groups were considering the first question, I also decided to bring forward a detailed case study of Malta’s CBW-relevant export control regulations. It was originally intended as a recapitulation of the various export control obligations and tools available during the second week. In the new context, the Maltese case study helped participants to understand the various previously introduced regulatory elements as part of a comprehensive whole. This shift had a major impact on how they approached the five questions.

Discussions based on the five questions continued the next day and into the next week. They replaced the lectures on national implementation and regulations as these topics were now dealt with in an interactive way.

With hindsight, the first decision was key from an educational viewpoint. Instead of aiming for information comprehensiveness, the target of the exercise—and by extension, of the whole course—became impact on the audience. The flowcharts the working groups drew collectively may have been imperfect, but they reflected the participants’ progressive understanding of issues and of their roles and responsibilities. What lacked in completeness or maybe even accuracy was compensated by their newly acquired ability to search for and validate information independently.

Research and structured searches

The first week of the Executive Course revealed weaknesses in research in general and conducting structured searches in particular. As noted above, the problem was not unanticipated. However, given the emphasis on interactive learning, it became more acute as the days passed. Among the challenges identified were limited awareness of the hierarchy of documents and information sources, lack of verification of the date of an information source, no background research into the information source, and most importantly, the absence of structured search methods. The interrelationship among those challenges was also clear. Whereas initially shortcomings and contradictions were pointed out to participants, by the weekend it had become evident that the deficiencies were structural rather than incidental. The insights informed the decision to devote a session to structured search methodology and adjust planned breakout group exercises to maximise the number of structured searches. Most of the second Thursday was dedicated to those goals.

Following an introduction and some basic exercises on structured searches, Kai Ilchmann introduced UN Security Council Resolution 1540, the work of the 1540 Committee and the matrices countries must use to report their fulfilment of Resolution 1540 obligations. Next participants working in breakout groups had to build country profiles using structured search methods. To several among them some results were surprising: their country had long ago updated national legislation and regulations, but not reported those to the 1540 Committee. They intended to contact the responsible agency.

During the afternoon the breakout groups worked on specific tasks that integrated the knowledge and insights discussed over the previous week and a half and research and analytical methods. Guidance during their work and plenary discussions of group presentations helped to consolidate understandings and methodologies and fill any remaining gaps.

Conclusions

The Executive Course achieved both aims. Participants indicated their interest in follow-up, both in terms of exploring further regional cooperation in raising awareness and education and possible follow-on activities in other Central Asian countries.

As a test-run for the full master’s course, the two weeks in Nur-Sultan were immensely useful. Its greatest impact was highly increased awareness among all participants of the issues involved in managing dual-use technology transfers. They grasped the complexity of the subject matter, understood the great variety of tools, and the importance of their integration. Practical examples introduced via a variety of interactive exercises made the issues concrete. Collaboration in breakout groups enabled people from different professional, academic and cultural backgrounds and with different levels of understanding of the topics to share experiences and knowledge.

The course faced several challenges. Given its length and intensity, the limited advance information about participants available to the lecturers handicapped lecture planning. All of the issues that could have become problematic, such as language, knowledge levels and research methods, had already been anticipated before the start of the course. The circumstances and the intensity with which they manifested themselves occasionally caused surprises. Via instantaneous evaluation and consultation among the lecturers (e.g. during coffee and lunch breaks) and adaptation of lecture contents to circumstances the problems were overcome without affecting the course goals.

Arguably the greatest challenge came at the end of the first week when it became clear that participants were not connecting the various elements discussed over the previous days. Signs had been emerging that following presentations and introduction of examples, the new knowledge was not being utilised in subsequent interactive exercises. The decision in the spur of the moment to radically alter the educational approach from lecturing—case study/exercises/knowledge integration (in this particular case, risk mitigation and role of national regulatory frameworks/Rabta historical example/discussion of tools/Malta case study)—to full interactive engagement with the participants—case study/targeted questions/knowledge integration/group discussions/plenary reporting/shared discovery (Rabta case study + questions/Malta case study/questions addressed in breakout groups/plenary presentation and discussion of answers/creating flowcharts)—changed the course dynamic. Variations of this approach were deployed during most of the second week with positive outcomes.

The shift had one significant implication: the emphasis came to lie with building capacities for research and analysis in the specific area of dual-use technology transfer controls rather than on transmitting a comprehensive information package.