A Middle East Zone Free from Non-conventional Weapons (2)

Part 2: Treaties governing chemical and biological weapons

In November 2019 a conference at the United Nations in New York marked a fresh round of diplomatic efforts to eliminate non-conventional arms – essentially nuclear weapons, and to a lesser extent chemical and biological weapons (CBW) – from the military arsenals in the Middle East.

This article is the second in a series of blog postings exploring the opportunities and challenges to ensure that the regional risks of CBW threats and use – chemical weapons (CW) were and, as I am writing, are part of conflicts in the Middle East – are banished once and for all.

Legal constraints on CBW

Legal constraints on CBW go back a long way. Before the acceptance of the germ theory at the end of the 19th century, the term ‘poison’ covered a broad range of noxious substances found in nature. They included toxic substances from the animal, mineral and plant kingdoms as well as disease (based on the then prevailing miasmic theory that poisonous matter in the air caused infection). Through the establishment of chemistry as a scientific discipline and its subsequent fast-growing commercial application in the industry, the meaning of poison (derived from nature) and asphyxiating gases (the product of science, technology and industry) gradually bifurcated.

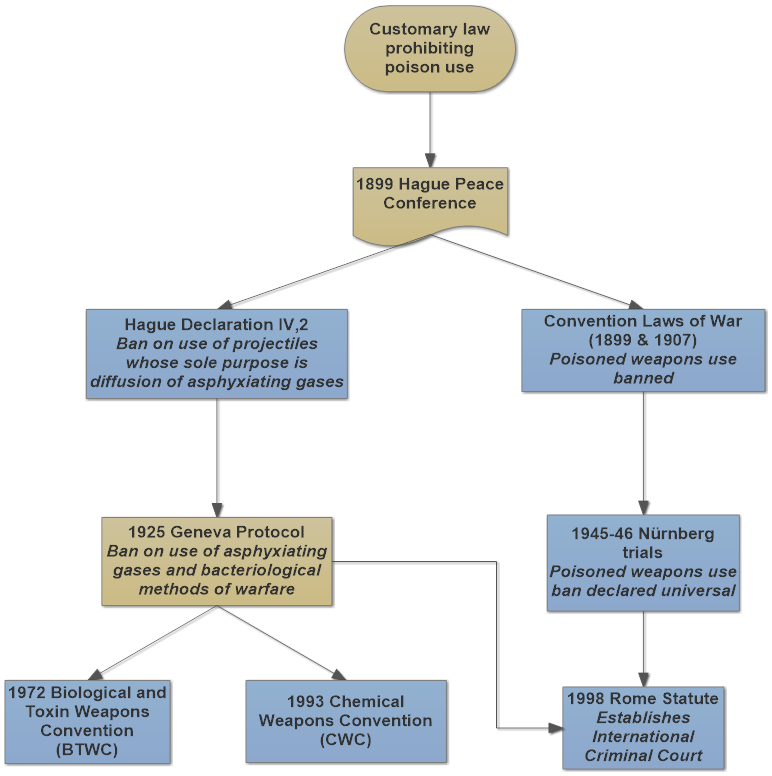

The semantic differentiation explains why diplomats at the 1899 Hague Peace Conference adopted two prohibitions, the century-old ban on the use of poisons and poisoned weapons in the Hague Convention (II) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and the Declaration (IV, 2) on the Use of Projectiles the Object of Which is the Diffusion of Asphyxiating or Deleterious Gases. Most importantly, the delegates adopted the poison provision without any debate, indicating that the prohibition belonged to the core of customary law, whereas the proposal to restrict the use of asphyxiating gases provoked substantial discussion. Ultimately, the participating countries did not unanimously adopt the declaration because it could not be demonstrated that the use of a type of weaponry that did not yet exist would be more inhumane than other modes of warfare. (For a more detailed overview: Jean Pascal Zanders (2003), International Norms Against Chemical And Biological Warfare: An Ambiguous Legacy.)

The Hague Declaration eventually led to the 1925 Geneva Protocol, which in its turn laid the foundation for the 1972 Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) and the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).

After the Second World War the court at the Nürnberg Trial declared the Hague Convention on the Laws and Customs of War (as adopted at the 1907 Hague Peace Conference) to be universally applicable. Consequently, the prohibition on the use of poisons and poisoned weapons applied to all countries, irrespective of whether they were party to the agreement or not.

International agreements against CBW currently in force

Three documents enshrine the norm against CBW today:

- The 1925 Geneva Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare today applies to both international and non-international armed conflicts. The document belongs to the laws of war (international humanitarian law). It does not set any restrictions on CBW acquisition and possession. During its negotiation as part of a conference to restrict the arms trade under the auspices of the League of Nations, negotiators were unable to prohibit the transfer of CW because of the widespread industrial and commercial use of some of the warfare agents used in the First World War. By designating the agreement a ‘Protocol’, the delegates signalled that the disarmament conference then under preparation should investigate the matter further (which the League of Nations did in committees). The language of the Geneva Protocol has shaped the framing of the relevant provisions in the 1998 Statute of Rome that established the International Criminal Court. The Geneva Protocol also provided the legal foundation for the UN Secretary-General (UNSG) to set up a Mechanism for Investigation of Alleged Use of Chemical and Biological Weapons during the 1980–88 Iran-Iraq war, The so-called UNSG Mechanism is still being further developed, especially with regard to possible biological weapon (BW) threats and use since the entry into force of the CWC.

- The 1972 Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction was the first multilateral legal instrument to prohibit an entire class of weaponry. The BTWC belongs to disarmament law: parties commit themselves individually to never under any circumstances develop, produce or otherwise acquire, or stockpile BW. Neither the title nor the first article of the convention containing the core prohibition refer to BW use. As BW discussions had been separated from those on CW, negotiators did not wish to undermine the authority of the Geneva Protocol that covered both arms categories. At the Fourth Review Conference in 1996, states parties adopted language making clear that the prohibition unambiguously includes BW use too. States parties decided on the establishment of an Implementation Support Unit (ISU) at the Sixth Review Conference in 2006.

- The 1993 Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction is by far the most comprehensive weapon control treaty in force. Its core prohibition includes CW use. The treaty provides for a comprehensive verification machinery that foresees oversight for the destruction of existing CW stockpiles and related equipment, sites and infrastructure, on the one hand, and manages, reviews and examines through inspections national declarations on treaty-relevant activities and industry production, on the other hand. A dedicated international body, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) oversees treaty implementation. It also has the capacity to investigate alleged CW use. It helps to build national capacities in states parties to fully implement the convention, promotes the peaceful uses of chemistry, and can provide emergency assistance in the case of a chemical attack or CW threat.

Differences between the CBW and nuclear weapon control regimes

Contrary to the often-heard complaint that the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty foresees different rights and obligations for the five nuclear weapon states and the other non-nuclear weapon states, the BTWC and CWC are entirely non-discriminatory. As disarmament treaties, no party can have a BW or CW. All states have same obligations and enjoy the same rights. Under either convention, they all have a single vote. Whereas the BTWC meetings require decisions by consensus, majority voting is possible in the OPCW decision-making organs, namely the Executive Council and the Conference of States Parties.

In contrast to the plethora of global, regional and bilateral agreements that regulate nuclear weapons, the BTWC and CWC represent single integrated treaty systems (SITS). This means that there are no legal documents with different purpose or obligations binding differing subsets of the world’s states.

Given the universal reach of both SITS, there also exist no regional CBW-free zones. However, prior to the CWC’s opening for signature in January 1993, states in several parts of the world entered into bilateral, regional or sub-regional agreements. Signatories basically declared that they did not possess CW or that they would jointly endeavour to eliminate them. They also committed themselves to become a party to the convention. Before the collapse of the negotiations in 2001, a similar process had taken off in anticipation of the opening for signature of the legally binding protocol to the BTWC. Such commitments – pre-nuptials, so to speak – aim to eliminate any security disadvantages among rivalling states that might arise from joining a disarmament treaty.

Status of the CBW treaties

The table below reflects the situation on 9 February 2020:

| Geneva Protocol | BTWC | CWC | |

| Opening for signature | 17 June 1925 | 10 April 1972 | 13-15 January 1993 |

| Entry into force | 8 February 1928 | 26 March 1975 | 29 April 1997 |

| Depositary | France | Russia, UK, USA | UNSG |

| States parties | 142 | 183 | 193 |

| Signatory states | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Non-signatory states | 55 | 10 | 3 |

The number of states parties to the CWC (or OPCW members) equals the number of members to the United Nations (193).

However, two UN observer states (Holy See and State of Palestine) and two non-UN members (Cook Islands and Niue) also joined the CWC.

The total number of countries relevant for the CBW treaties is therefore 197.

Status of the CBW treaties in the Middle East

In accordance with the definition of the Middle East by the International Atomic Energy Agency that serves as basis for the new conference seeking to create a zone free of non-conventional weapons and in view of the State of Palestine having achieved non-member observer State status in the United Nations, the region comprises 24 countries.

The following table summarises the status of the three agreements in the Middle East (P = Party; S = Signatory; N = Non-signatory).

| Geneva Protocol | BTWC | CWC | |

| Algeria | P | P | P |

| Bahrain | P | P | P |

| Comoros | N | N | P |

| Djibouti | N | N | P |

| Egypt | P | S | N |

| Iran (Islamic Republic of) | P | P | P |

| Iraq | P | P | P |

| Israel | P | N | S |

| Jordan | P | P | P |

| Kuwait | P | P | P |

| Lebanon | P | P | P |

| Libya | P | P | P |

| Mauritania | N | P | P |

| Morocco | P | P | P |

| Oman | N | P | P |

| Qatar | P | P | P |

| Saudi Arabia | P | P | P |

| Somalia |

N | S | P |

| State of Palestine | P | P | P |

| Sudan | P | P | P |

| Syrian Arab Republic | P | S | P |

| Tunisia | P | P | P |

| United Arab Emirates | N | P | P |

| Yemen | P | P | P |

Six states in the Middle East are not party to the Geneva Protocol: Comoros, Djibouti, Mauritania, Oman, Somalia and the United Arab Emirates.

Of the six states not party to the BTWC, three are signatories (Egypt, Somalia and Syria) and three are non-signatories (Comoros, Djibouti and Israel).

Egypt has neither signed nor acceded to the CWC, while Israel still has to ratify the convention.

Notwithstanding, the table also shows that not a single Middle Eastern state is not covered by at least one legal constraint on CBW. This observation represents an important building block for starting to construct a zone free of non-conventional weapons.