A Middle East Zone Free from Non-conventional Weapons (3)

Part 3: Defining the Middle East, a loaded question

In November 2019 a conference at the United Nations in New York (report here) marked a fresh round of diplomatic efforts to eliminate non-conventional arms – essentially nuclear weapons, and to a lesser extent chemical and biological weapons (CBW) – from the military arsenals in the Middle East. As indicated in the second part of this series, participants in the new conference series depart from the definition of the Middle East used by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

At the UN Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) seminar ‘The Middle East Weapons of Mass Destruction Free Zone, 2020 NPT Review Conference, and Pathways Forward’ held on 6 February, I asked whether circumscription of the region came down to the members of the League of Arab States (LAS), plus Iran and Israel. In reply I was referred to ‘the’ IAEA definition.

What IAEA definition?

Searches for an IAEA document reflecting a decision on the formal circumscription of the region turned up empty. So far, the best I have come up with are a series of annual reports by the agency’s Director General entitled ‘Application of IAEA Safeguards in the Middle East’ that simply list 23 states (e.g. IAEA document GOV/2011/55-GC(55)/23 of 2 September 2011, p. 2, fn. 1). The footnote began appearing towards the end of the 2000s, ahead of the 2010 Review Conference (RevCon) of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). A table with the safeguards agreements for states in the Middle East region attached to the addendum to the 2013 report (IAEA document GOV/2013/33/Add.1-GC(57)/10/Add.1, Attachment 2) lists the same states.

The listing draws on an earlier document, entitled ‘Technical Study on Different Modalities of Application of Safeguards in the Middle-East’ (IAEA document GC(XXXIII)/887, 29 August 1989). That source is no longer obtainable from the IAEA website (URL references produce an error) and does not appear available elsewhere from the internet.

Additional online investigation confirms that the region has evolved as a concept. After the UN General Assembly (UNGA)’s adoption of resolution 3263 (XXIX) on 9 December 1974 commending a Nuclear Weapon Free Zone (NWFZ) for the Middle East, the United Nations and IAEA produced several reports and studies. These documents reveal considerable technical attention to the meaning of a NWFZ, the responsibilities of parties to such a zone, and the organisation of verification. However, their language tended to be much more circumspect when touching upon the zone’s geographic dimension.

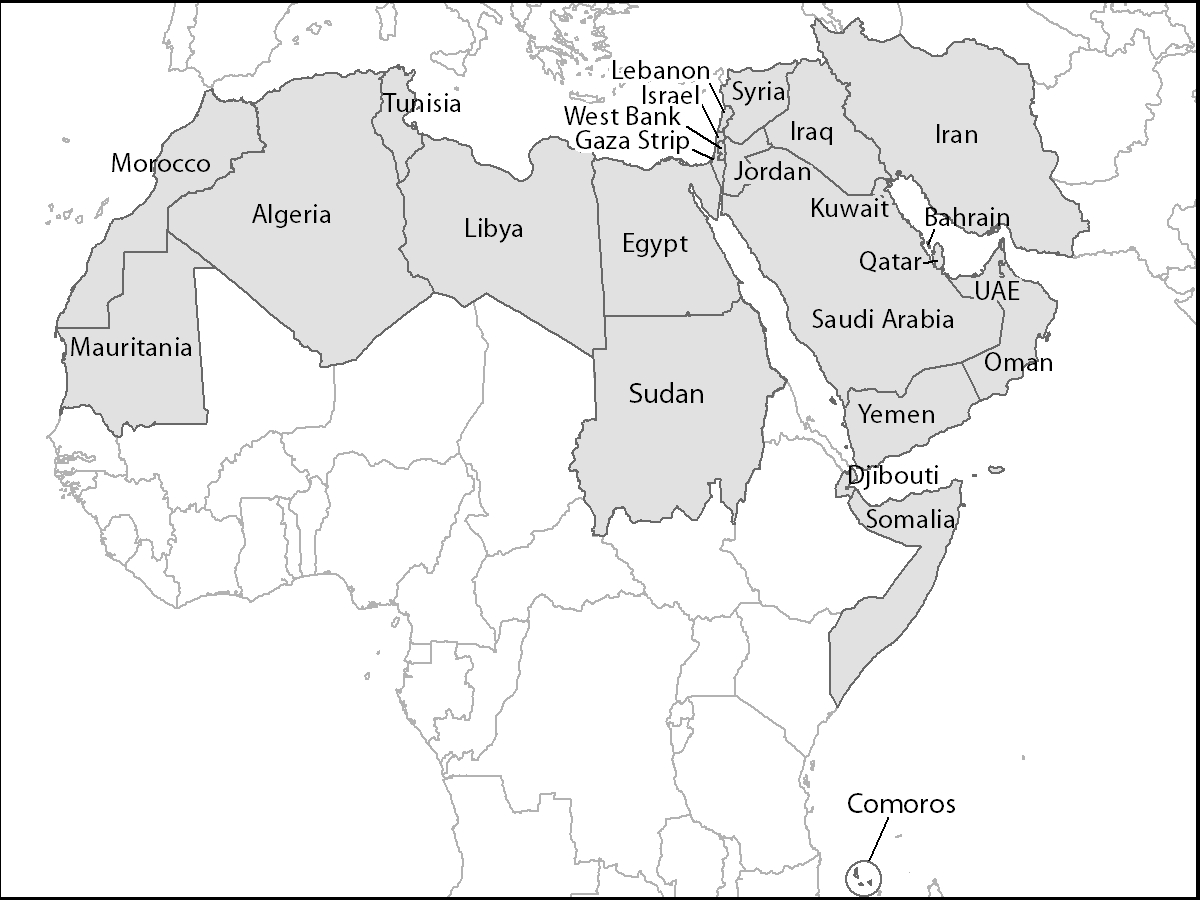

According to the Study on effective and verifiable measures which would facilitate the establishment of a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the Middle East prepared for the UN Secretary-General (UNSG) in 1990, the IAEA had identified ‘the area extending from the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya in the West, to the Islamic Republic of Iran in the East, and from Syria in the North to the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen in the South’ for the future zone. This depiction equally drew on the afore-mentioned IAEA Technical Study. Even so, the UNSG study viewed this circumscription as a working list, recognising that the NWFZ could expand in stages from the set of core countries to ultimately encompass ‘all states directly connected to current conflicts in the region’. By this, the authors meant all LAS members, Iran and Israel (p. 20, paras. 64-66).

However, the IAEA’s delineation seems to draw on an even earlier UNSG report to the Security Council (document S/11778, 28 July 1975). In fulfilment of the request in UNGA resolution 3263 (XXIX), the UNSG had invited Bahrain, Democratic Yemen, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the Syrian Arab Republic, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen to express their views on the idea of the zone. These countries all fall in the so-called ‘core’ area identified by the IAEA (Yemen reunified in 1990).

If the list the IAEA began using towards the end of the 2000s seemed to satisfy the circumscription of the Middle East region, Palestine was never named among the 23 states. It has been a LAS member since 1976.

On 29 November 2012 the UNGA adopted resolution A/RES/67/19 according Palestine UN non-member observer state status. With its newly acquired recognition, Palestine joined several multilateral weapon control treaties, including the NPT, Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) and the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). In fulfilment of its NPT obligations, it negotiated a safeguards agreement with the IAEA in 2018 to cover the small amounts of nuclear materials used in hospitals, universities and for agricultural and industrial purposes. Palestine and the IAEA signed the document on 18 June 2019. However, until today the state is not a member of the IAEA (see also below), and protests by Israel forced the IAEA to deny that the safeguards agreement entailed recognition of Palestine as a state.

In the September 2019 edition of the annual ‘Application of IAEA Safeguards in the Middle East’ report (document GOV/2019/35-GC(63)/14), the Director General described the Middle East region as ‘Members of the League of Arab States, the Islamic Republic of Iran and Israel’ (p.2, fn. 1). Probably a nice diplomatic solution to avoid listing Palestine as a Middle Eastern state.

All of which, of course, takes us back to my original question and begs why the answer could not simply have been ‘yes’. If there ever was an ‘IAEA definition’, then for sure the concept of the Middle East has evolved substantially over the past decades. Even up to last year.

A concept of the region and treaty participation

The brief historical reconstruction of political and diplomatic sensitivities in defining the region also reveals other complicating elements, namely the initial framing of the circumscription in the context of a NWFZ as well as the involvement by regional actors in treaties and institutions governing other arms categories.

The table below comprises six moments relevant to a NWFZ for the Middle East: entry into force (EIF) of the IAEA statutes (1957); EIF of the NPT (1970), the UNGA resolution on a NWFZ (1974); the broadening of that initiative to include CBW at the 1995 NPT RevCon; the decision to hold a conference on the NWFZ for the Middle East at the 2010 NPT RevCon; and the first meeting of the new conference series in 2019.

| IAEA | NPT | BTWC | CWC | |

| 1957 | 4 | – | – | – |

| 1970 | 14 (+10) | 8 | – | – |

| 1974 | 14 (+0) | 9 (+1) | – | – |

| 1995 | 17 (+3) | 20 (+11) | 12 | – |

| 2010 | 20 (+3) | 22 (+2) | 16 (+4) | 18 |

| 2019 | 21 (+1) | 23 (+1) | 18 (+2) | 22 (+3) |

The limited participation in the IAEA and the NPT, especially between 1974 and 1995, may explain the delicacy of naming countries in official documents and studies produced by the United Nations or the IAEA following the UNGA’s adoption of the NWFZ resolution in 1974. By way of illustration, Egypt, a key player in the initiative, had become an original IAEA member, but did not ratify the NPT until 1981. Even today, not every state in the region is a member of the IAEA. Somalia and Palestine remain outside the organisation, the latter country in spite of its recent safeguard agreements. The IAEA General Conference approved Comoros’ membership in 2014 but now awaits the country’s deposit of its instrument of accession. Israel, a member of the IAEA, is not a party to the NPT.

Diplomatic activity pressing the NWFZ benefited regional adherence to the NPT, which in turn reinforced the sense of ‘Middle East’. However, widening the original proposal in 1995 to also include CBW may have again complicated matters. The BTWC, CWC and the NPT place different types of requirements on states parties. Moreover, participation by Middle Eastern states in the treaties differs.

When Egypt launched the initiative barely half of the Middle Eastern region was party to the BTWC. Even today one quarter is still missing. In 1995 EIF of the CWC lay two years in the future, but its rate of universalisation, including in the Middle East, has been impressive.

There is, however, a different problem. When the CWC was opened for signature in January 1993, the LAS under Egypt’s impulse called for a boycott of the convention until Israel had joined the NPT. It repeated that call several times, but many members soon signalled their intention to become a party, thereby breaking the linkage. (See Zanders and French (April 1999) and Mills (August 2002)). Today, Egypt is the only holdout LAN member. Therefore, the question is whether and how the CWC can be linked to the zone free of non-conventional weapons in future negotiations.

Negotiating partners versus the zone

In conclusion: while we may have greater clarity about ‘the’ Middle Eastern region today, we should not confuse a regional circumscription enabling ownership of the process with the future boundaries of the Middle East zone free of non-conventional weapons. Israel did not turn up for the first meeting of the new conference.

Can the zone ever come into being without Israeli membership? If Israel stays obstinate, is it possible for the other invitees to design and offer a package of proposals that considers Israel’s legitimate security interests that might induce the country to become engaged in the process?

Iran did participate, but how does it define its security interests relative to the zone? Can the zone overcome sub-regional geopolitical rivalries among the Gulf countries? Will it offer enough security guarantees against extra-regional threats enabling the country to lift any uncertainty about the true nature of its nuclear activities?

Above all, as Harald Müller and Claudia Baumgart-Ochse wrote in a background paper back in 2011 (pp. 1-2):

Given the state of conflict, violence and mutual distrust in the region, it is highly improbable that a [Weapons of Mass Destruction Free Zone] can ever be established without a considerable change in the overall relationship between the states in the region that makes war between them highly unlikely. [...] Such a change would require the mutual recognition of all states in the region by all states in the region, within regionally agreed borders. To dispute the right of existence of a regional neighbour makes any process of disarmament a non-starter.

And then there is of course the question of countries not included in the current round of negotiations. Already after the 2010 NPT RevCon launched the idea of a special disarmament conference for the Middle East, the relevancy of Comoros and the exclusion of Turkey was questioned. Today, the place of Turkey again comes into the picture in view of the country’s assertiveness in neighbouring Syria, talk of possible withdrawal of nuclear weapons from US bases there, and noises of acquiring an autonomous nuclear capacity.