From irritant to tear-gas: the early story of why a toxic agent became non-lethal

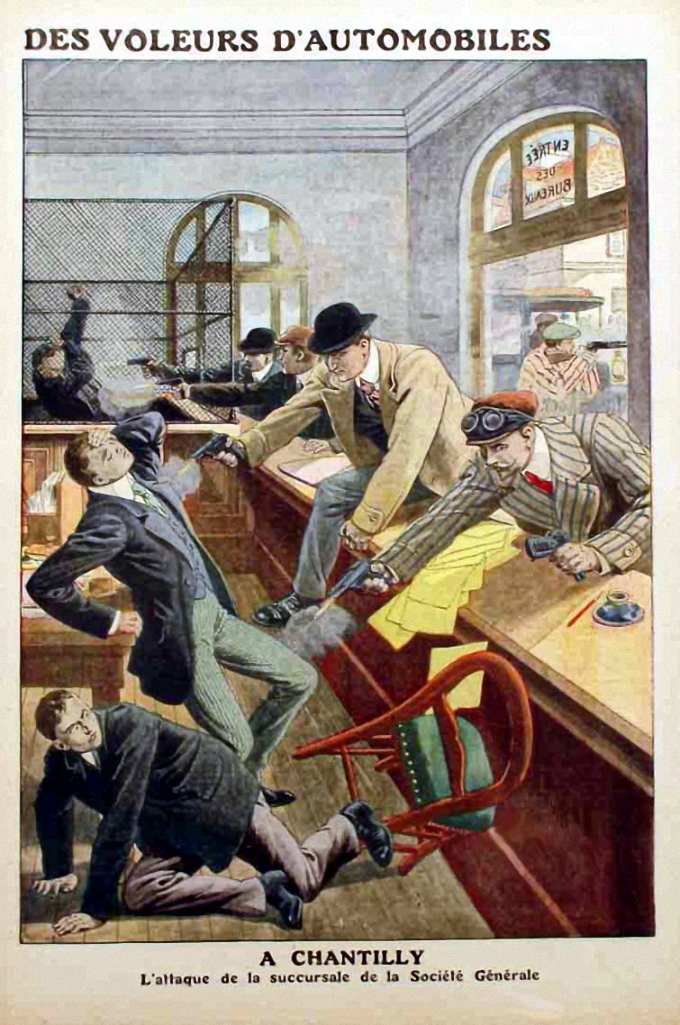

With the recent international attention to riot control agents (RCA) people have raised the question how their use against protesting civilians can be legal when the toxic agents are internationally banned from battlefields. Framed as such, the question is not entirely correct. In my previous blog posting I argued that outlawing RCAs for law enforcement and riot control based on the above reasoning may run into complications in the United States because the country still identifies operational military roles for irritants on the battlefield in contravention of the Chemical Weapons Convention. This article sketches the convoluted history of harassing agents …

Innocence Slaughtered: Introduction

Innocence Slaughtered will be published in December 2015 In November 2005 In Flanders Fields Museum organised and hosted an international conference in Ypres, entitled 1915: Innocence Slaughtered. The first major attack with chemical weapons, launched by Imperial German forces from their positions near Langemarck on the northern flank of the Ypres Salient on 22 April 1915, featured prominently among the presentations. I was also one of the speakers, but my address focussed on how to prevent a similar event with biological weapons. Indeed, it was one of the strengths of the conference not to remain stuck in a past of—at …

Innocence Slaughtered

Innocence Slaughtered Gas and the transformation of warfare and society Jean Pascal Zanders (ed) Publication: December 2015 Table of Contents Ahmet Üzümcü (Director-General Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons): Preface Jean Pascal Zanders: Introduction Jean Pascal Zanders: The Road to The Hague Olivier Lepick: Towards total war: Langemarck, 22 April 1915 Luc Vandeweyer: The Belgian Army and the gas attack on 22 April 1915 Dominiek Dendooven: 22 April 1915 – Eyewitness accounts of the first gas attack Julian Putkowski: Toxic Shock: The British Army’s reaction to German poison gas during the Second Battle of Ypres David Omissi: The Indian …

Innocence Slaughtered – Forthcoming book

The introduction of chemical warfare to the battlefield on 22 April 1915 changed the face of total warfare. Not only did it bring science to combat, it was both the product of societal transformation and a shaper of the 20th century societies. This collaborative work investigates the unfolding catastrophe that the unleashing of chlorine against the Allied positions meant for individual soldiers and civilians. It describes the hesitation on the German side about the effectiveness, and hence impact on combat operations of the weapon whilst reflecting on the lack of Allied response to the many intelligence pointers that something significant …

Innocence Slaughtered – Book launch at OPCW

Described by Ambassador Ahmet Üzümcü, Director-General of the OPCW, as a ‘remarkable compilation of materials, rich in detail and edited in the finest traditions of highly readable scholarship’, Innocence Slaughtered is a new book that will launch with a panel discussion on 2 December, from 13.00-15.00 at this year’s Conference of States Parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention. Edited by Dr Jean Pascal Zanders, the book features the writings of eleven experts and historians on gas warfare and chemical weapons and is being published to coincide with the first phosgene attack in WWI on 19 December 1915. The launch event …

Innocence Slaughtered: Book launch at the OPCW

Wednesday, 2 December, Innocence Slaughtered finally saw the light. At a lunch-time side event at the OPCW Headquarters during the Conference of the States Parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention in The Hague, the book got presented to an audience of some 40 people. Ambassador Ahmet Üzümcü, Director-General of the OPCW, opened the proceedings, followed by Mr Jef Verschoore, Deputy-Mayor of Ieper and Chairperson of the In Flanders Fields museum, sponsor of the publication project. One of the chapter authors, medical historian Dr Leo van Bergen reflected on the deeper meaning of the book’s title: Innocence Slaughtered. Mr Dominiek …

After 99 years, back to chlorine

Today is the 99th anniversary of the first massive chemical warfare attack. The agent of choice was chlorine. About 150 tonnes of the chemical was released simultaneously from around 6,000 cylinders over a length of 7 kilometres just north of Ypres. Lutz Haber—son of the German chemical warfare pioneer, Fritz Haber—described the opening scenes in his book The Poisonous Cloud (Clarendon Press, 1986): The cloud advanced slowly, moving at about 0.5 m/sec (just over 1 mph). It was white at first, owing to the condensation of the moisture in the surrounding air and, as the volume increased, it turned yellow-green. …

When did you last hear 'gas' and 'humane' in the same sentence?

This morning, I came across an item on the BBC website entitled: Princess Anne: Gassing badgers is most humane way to cull. According to the piece, Princess Royal’s comments came after the British government said it would not expand badger culling from two pilot culls aimed at reducing TB in cattle. Interest groups of course welcomed her remarks. As a representative of the National Farmers’ Union said in a BBC radio interview ‘The Princess Royal is noted for outspoken views and her forthright honesty. I think it’s an option that needs looking at. And provided we can tick all the …

From Flanders' entrenched politics

[Updated: 9 March 2014] Next month, on the 22nd, it will be the 99th anniversary of the start of modern chemical warfare. The salient around the Flemish town of Ieper offered the perfect location: its northern edge was the only place along the Western front where German troops did not face the prevailing south-westerly winds that could have blown back the chlorine cloud. Later, of course, shells replaced gas cloud attacks. Shells imply depots, including ones close to the trenches. In Flanders it is not uncommon to still uncover duds—shells that failed to detonate because of malfunction or simply because …